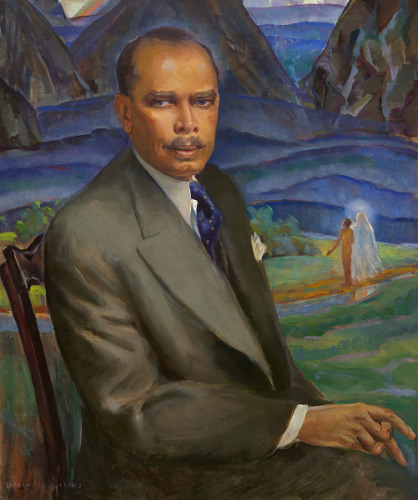

James Weldon Johnson, Writer and Civil Rights Activist

Feb 19, 2021

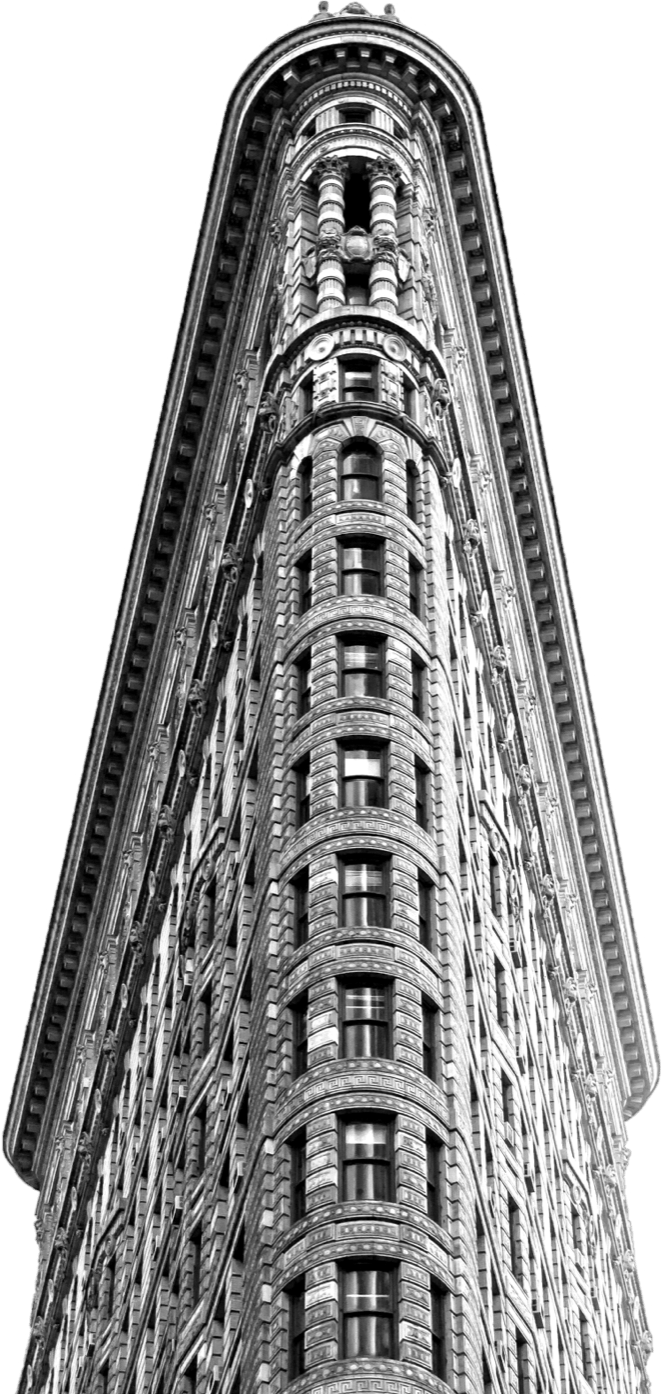

In honor of Black History Month, the Flatiron Partnership takes a look at the trailblazing ties of civil rights activist and writer James Weldon Johnson in the neighborhood. Johnson’s legacy includes his vision for the NAACP’s Silent Protest Parade on Fifth Avenue in 1917, and composing a campaign song for presidential candidate and Flatiron native Theodore Roosevelt in 1904.

Photo Credit: Theodore Roosevelt Center

When James Weldon Johnson and his younger brother Rosamond left their hometown of Jacksonville, Florida for New York City in 1901, they set out for careers as Broadway music songwriters. The siblings had been “raised without a sense of limitations amid a society focused on segregating African Americans,” notes the website, Biography. Their father James was a freeborn Virginian hotel head waiter, and their Bahamian mother Helen was a teacher and musician.

Johnson, who was born in 1871, graduated from Atlanta University in 1894. The following year, he launched The Daily American newspaper, and in 1897, became the first African American to pass Florida’s bar exam since the Reconstruction era, notes Britanncia. Rosamond, who was two years younger and a music prodigy, had studied at the New England Conservatory. The pair’s interests in writing and music lead to their collaboration “Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing,” a poem written by Johnson and set to music by Rosamond.

Photo Credit: Wikipedia

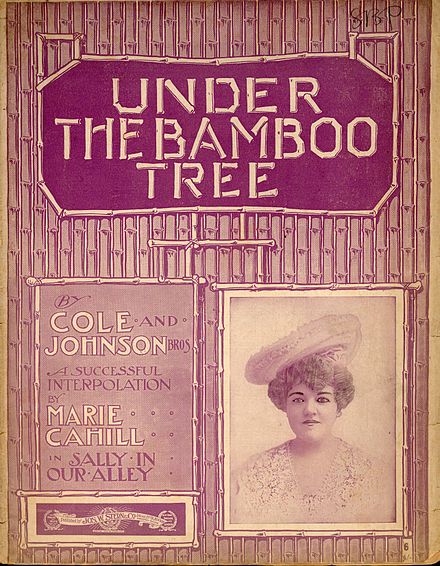

The brothers then teamed with Robert Cole to write theater tunes. In a five-year span, “they composed some 200 songs for Broadway and other musical productions, including such hit numbers as “Under the Bamboo Tree,” “The Old Flag Never Touched the Ground,” and “Didn’t He Ramble,” notes The Poetry Foundation. “The trio, who soon became known as “Those Ebony Offenbachs,” avoided writing for racially exploitative minstrel shows but often found themselves obliged to present simplified and stereotyped images of rural Black life to suit white audiences. But the Johnsons and Cole also produced works like the six-song suite titled The Evolution of Ragtime that helped document and expose important Black musical idioms.”

During this period, the 1904 presidential campaign was also underway. Johnson had been recruited to become chairman of the house committee for New York City’s newly formed Colored Republican Club on West 53rd Street. “The campaign to elect Theodore Roosevelt to succeed himself in the Presidency was just beginning to warm up,” wrote Johnson in his 1933 autobiography Along This Way. Roosevelt, a progressive Republican, was also a New York City native who had grown up in a brownstone located on East 20th Street. When asked by one of the club officials to “give us something good to sing” for Roosevelt’s campaign, the team of Cole and Johnson delivered “You’re All Right Teddy” within days, reported The Sun on July 31, 1904.

“To appreciate that song you have to hear it with music,” according to The Sun about the melody’s presentation before a club audience.“There is a jubilee shout about the chorus which carries you off your feet. The quartet sang the words and the club chorus of fifty voices came into the chorus, and by the third repetition everyone was singing it. They encored and encored until the quartet ran out of words and [James] Johnson had to improvise on the spot. Then the audience tore the shingles down with applause.” Next came the candidate’s seal of approval. “Rosamond carefully made a manuscript copy, which was sent to Mr. Roosevelt,” remembered James. “He wrote complimenting us on having written ‘a bully good song.’”

Roosevelt was elected and upon his return to the White House, James was soon offered positions in the administration. Reportedly fluent in French and Spanish, Johnson was selected to serve as consul to Puerto Cabello, Venezuela in 1906, followed by Corinto, Nicaragua in 1909. He resigned from the latter post in 1913 when Woodrow Wilson, a Democrat, was elected President, and reportedly on the belief opportunities for advancement were limited due to racism.

Photo Credit: Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery

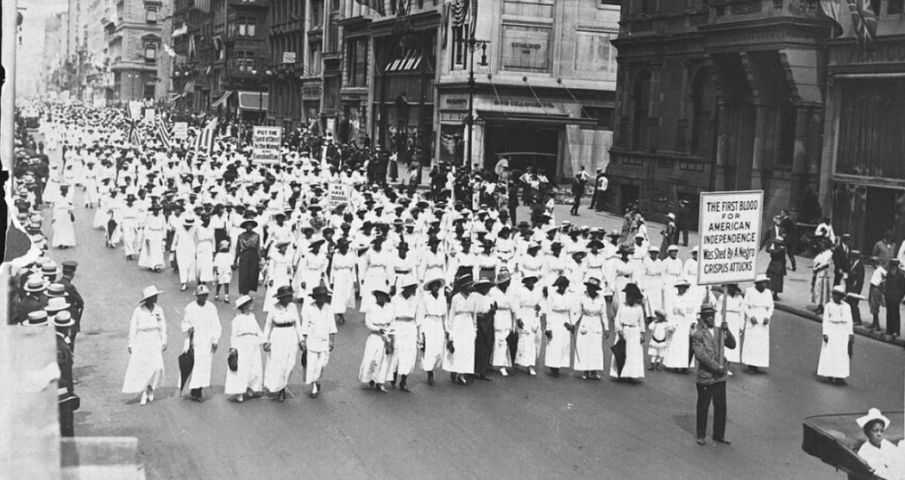

In 1916, Johnson was named afield secretaryfor the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). “Johnson worked at opening new branches and expanding membership,” notes naacp.org. “In 1920, the NAACP appointed him executive secretary. In this position, he was able to bring attention to racism, lynching, and segregation.” Johnson’s efforts included launching the idea for the NAACP’s Silent Protest Parade on July 28, 1917 because of racially motivated acts of violence against Black people in East St. Louis, Illinois on July 2nd.

Photo Credit: Miami Herald

The Fifth Avenue march began at 59th Street and concluded at 23rd Street. “On July 28, nine or ten thousand Negroes marched silently down Fifth Avenue to the sound only of muffled drums,” recalled Johnson. “The procession was headed by children, some of them not older than six, dressed in white. These were followed by the women dressed in white, and bringing up the rear came the men in dark clothes. The streets of New York have witnessed many strange sights, but I judge, never one stranger than this; certainly, never one more impressive. The parade moved in silence and was watched in silence. Among the watchers were those with tears in their eyes.”

Photo Credit: Penguin Random House

After 10 years at the NAACP, Johnson resigned to pursue other job opportunities. They included a creative writing professorship at Fisk University, the historically Black college in Nashville, Tennessee, in 1930, and as a visiting professor on the same subject at New York University beginning in 1934. Over the years, Johnson had either written or edited numerous works of literature such as his 1912 novel The Autobiography of an Ex-Colored Man, and the 1930 book Black Manhattan, which detailed African American life during the Harlem Renaissance.

Johnson was also a Harlem resident and had married Grace Nail, the daughter of a real estate developer, in 1910. Said Johnson of the time the couple first met, “She carried herself like a princess.” Sadly, on June 26, 1938 when the Johnsons were on vacation at their Wiscasset, Maine summer home, their car was hit by a train at a grade crossing. Johnson, who was then 67, had been killed and his wife suffered severe injuries.

Two days later following the loss of James Weldon Johnson, The New York Times noted that “few lives are so rich in various experience and accomplishment as his, so tragically ended.” In a pledge about his life as a Black man, the writer and civil rights activist once wrote: “I will not allow one prejudiced person or one million or one hundred million to blight my life. I will not let prejudice or any of its attendant humiliations and injustices bear me down to spiritual defeat. My inner life is mine, and I shall defend and maintain its integrity against all the powers of hell.”

Header Photo: James Weldon Johnson Memorial Collection of African American Arts

Thumbnail Photo: Poetry Foundations