Turning Back the Hands of Time

Oct 26, 2018

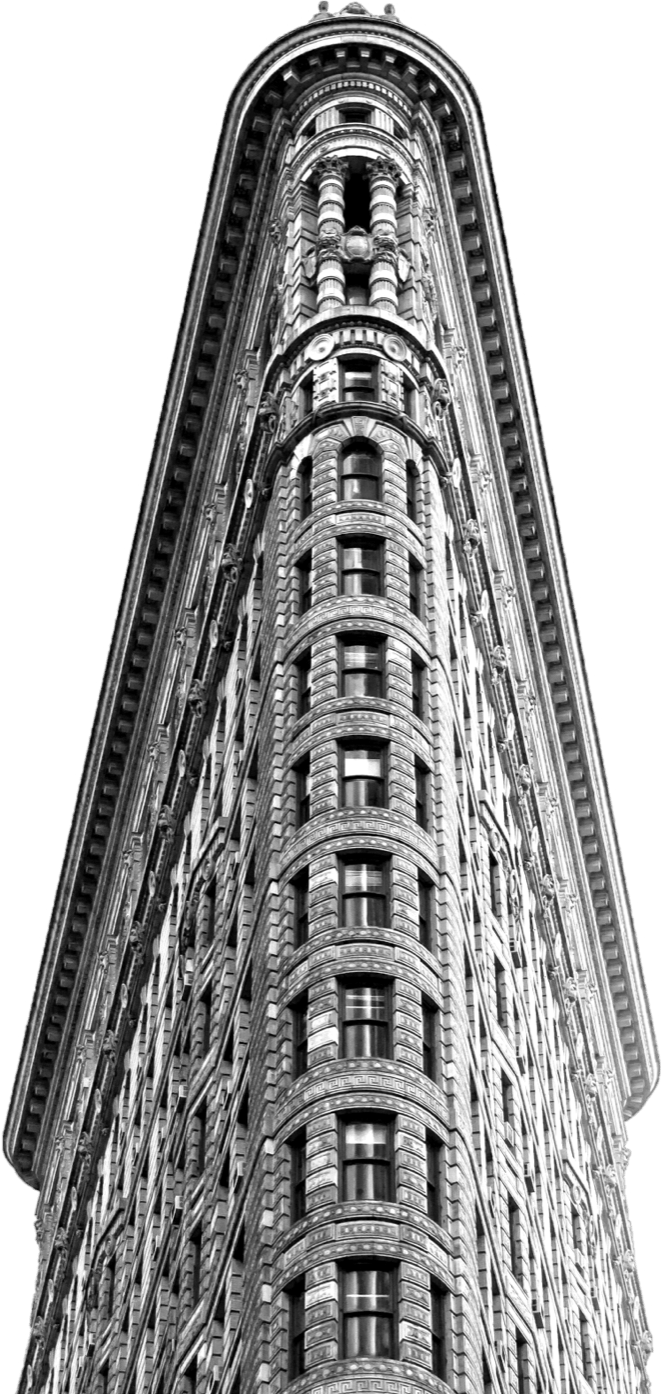

Sunday, November 4th marks the return to Standard Time. This year is also the centennial anniversary of the Calder Act, or Standard Time Act of 1918, a U.S. Federal law that implemented Standard and Daylight Saving Time. As we prepare to set clocks back one hour this weekend, the Flatiron/23rd Street Partnership takes a look at a few notable street clocks that have appeared in the neighborhood.

Cast-iron street clocks were a form of novel advertising that began during the mid-19th century, according to New York City’s Landmarks Preservation Commission. “A small business concern that stayed in the same location year after year would buy a street clock and install it directly in front of the store, often painting the name of the business onto the clock face,” noted the Commission in their 1981 Landmark Designation Report about the Fifth Avenue Clock Building at 200 Fifth Avenue. “When the business owners moved, they usually took their clocks with them.”

When the MetLife Clock made its debut in 1909, it became known as the world’s largest timepiece. The community’s most prominent clock, located at the top of the MetLife Tower at 5 Madison Avenue, between 23rd and 24th Streets, features four dials. Each of the clock’s four faces measures 26.5 feet in diameter, with minute hands 17-feet long and hour hands 13 feet and 4 inches. The cast bronze numerals are four-feet high.

The New York Times on May 26, 1996 described the Tower, which was designed by architects N. LeBrun & Sons and based on the Campanile at the Piazza San Marco in Venice, as “all white Tuckahoe marble, with a giant four-faced clock and a beacon at the top.” It’s also where the quarter hour was signaled at night by flashing lights and Westminster Chimes played every hour from 9 am to 10 pm.

On August 22, 2001, the Times also wrote that the Clock “is not a timepiece as much as a work of architecture, hugely scaled yet intricately detailed. In each dial face are three delicate, concentric necklaces of cornflower blue and turquoise. These are made of countless thousands of tesserae, small mosaic tiles laid in a radial pattern.”

“For those scurrying too quickly to check its mammoth dials, chimes mark every hour with a series of hard-to-miss gongs,’’ reported the New York Daily News on April 12, 1998. “The building is also known for its light beacon; in the days before radio, mariners used its light to guide their ships into New York Harbor. The beacon also served as the inspiration for the famous ad slogan: ‘The light that never fails.’ ”

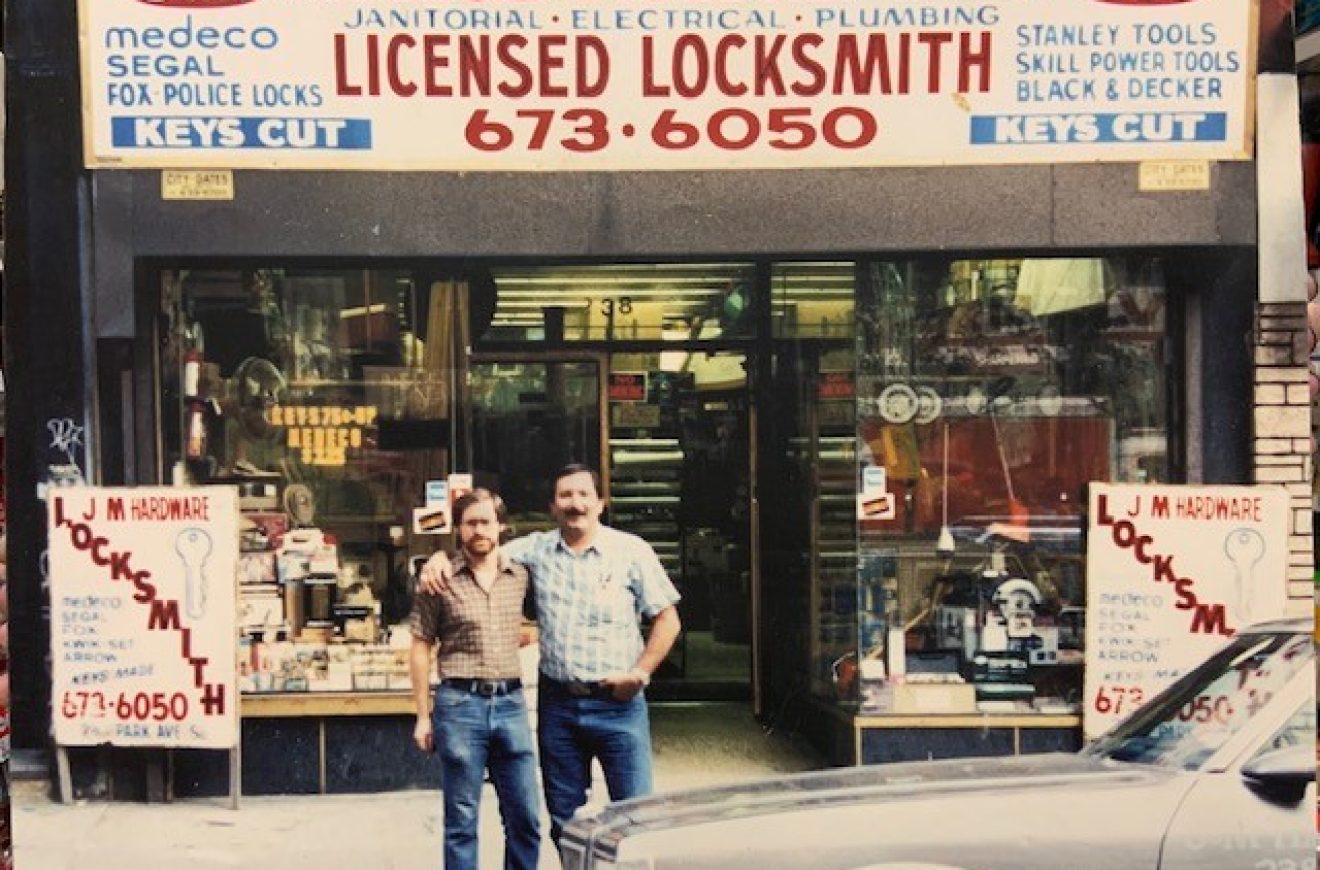

The Fifth Avenue Clock, located at 200 Fifth Avenue, was also installed in 1909 with the construction of the Fifth Avenue Building. It features the the building’s name on its face. As “a stylish advertisement, the ornate cast-iron clock is composed of a rectangular, classically ornamented base and a faulted Ionic column with a Scammozi capital,” wrote Barbaralee Diamonstein-Spielvogel in her book The Landmarks of New York, Fifth Edition: An Illustrated Record of the City’s Historic Buildings. “Its dials are marked with Roman numerals, framed by wreaths of oak leaves, and crowned by a cartouche.”

The double-faced clock with “Fifth Avenue Building” marking its dial stands 19-feet high and was created and installed by Hecla Iron Works. The Fifth Avenue Building was designed by architects Robert Maynicke and Julius Franke. The clock replaced a previous one that had been installed by the famed Fifth Avenue Hotel, a former occupant of the commercial property once owned by real estate developer Amos Richards Eno.

In August 1981, the clock was designated a historic landmark by the Landmarks Preservation Commission. “On the basis of a careful consideration of the history, the architecture and other features of this structure,” the Commission declared in its report, “the Landmarks Preservation Commission finds that the Sidewalk Clock, 200 Fifth Avenue has a special character, special historical and aesthetic interest and value as part of the development, heritage and cultural characteristics of New York City.”

When legendary jeweler Tiffany & Co. relocated its corporate offices from Midtown to 200 Fifth Avenue in 2011, the business decided to refurbish the clock, which had “fallen into disrepair over the years after an auto accident damaged the clock’s base and left it in poor working condition,” reported the New York Post on June 11, 2001.

A few doors northward, the Lincoln Trust Company occupied a seven-story office building at 208 Fifth Avenue. Designed by architects Charles Berg and Edward Clark, the building was constructed between 1893 and 1894 and also shared the address 1130 Broadway. Notable and wealthy Fifth Avenue Hotel proprietor Alfred B. Darling was the property’s owner.

“The building went through from Fifth to Broadway,” says Miriam Berman, author of Madison Square: The Park and Its Celebrated Landmarks and a Flatiron/23rd Street Partnership walking tour guide, “and both façades were mirror images of each other—each featuring a ground floor entry with pediment and columns and a sidewalk clock.”

“The first two stories of both façades,” noted the Madison Square North Historic District Designation Report published by the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission in 2001, “were substantially altered in 1902 for the Lincoln Trust Co., which leased the space from the Estate of Alfred B. Darling.”

A sidewalk clock was also a form of business branding for restaurants, notes Berman. Dorlon’s Oyster House, which had the joint address of 6 and 7 East 23rd Street, between Broadway and Madison Avenue, “had a sidewalk clock to advertise their eatery—probably in about the 1890s,” says Berman.

William Grimes, author of Appetite City: A Culinary History of New York and a former New York Times restaurant critic noted that “big spenders went to Madison Square, where hotels like the Hoffman House and the Brunswick had fine restaurants, and, on the south side of the park, Dorlon’s specialized in oysters and grilled meats.”

In addition to shellfish, wrote Grimes, “patrons could order a porterhouse steak, fried tripe, or game in season, including canvasback duck, partridge, woodcock, or venison.” To accompany a meal at Dorlon’s, diners could imbibe beer, wine, or quality champagnes such as Veuve Clicquot, which then cost $2.00 a pint or $4.00 for a quart. They could also cap off the evening with a slice of pie or strawberry shortcake for dessert—a perfect end to a night well spent during a treasured time in the Flatiron District.

Photo Credit: MetLife Clock Tower, Martin Seck